For some people, change is a matter of life or death. But why is it still so difficult?

Improvisation

Love and constraints

Great expectations

The survey says...

The user is drunk

Designed problems

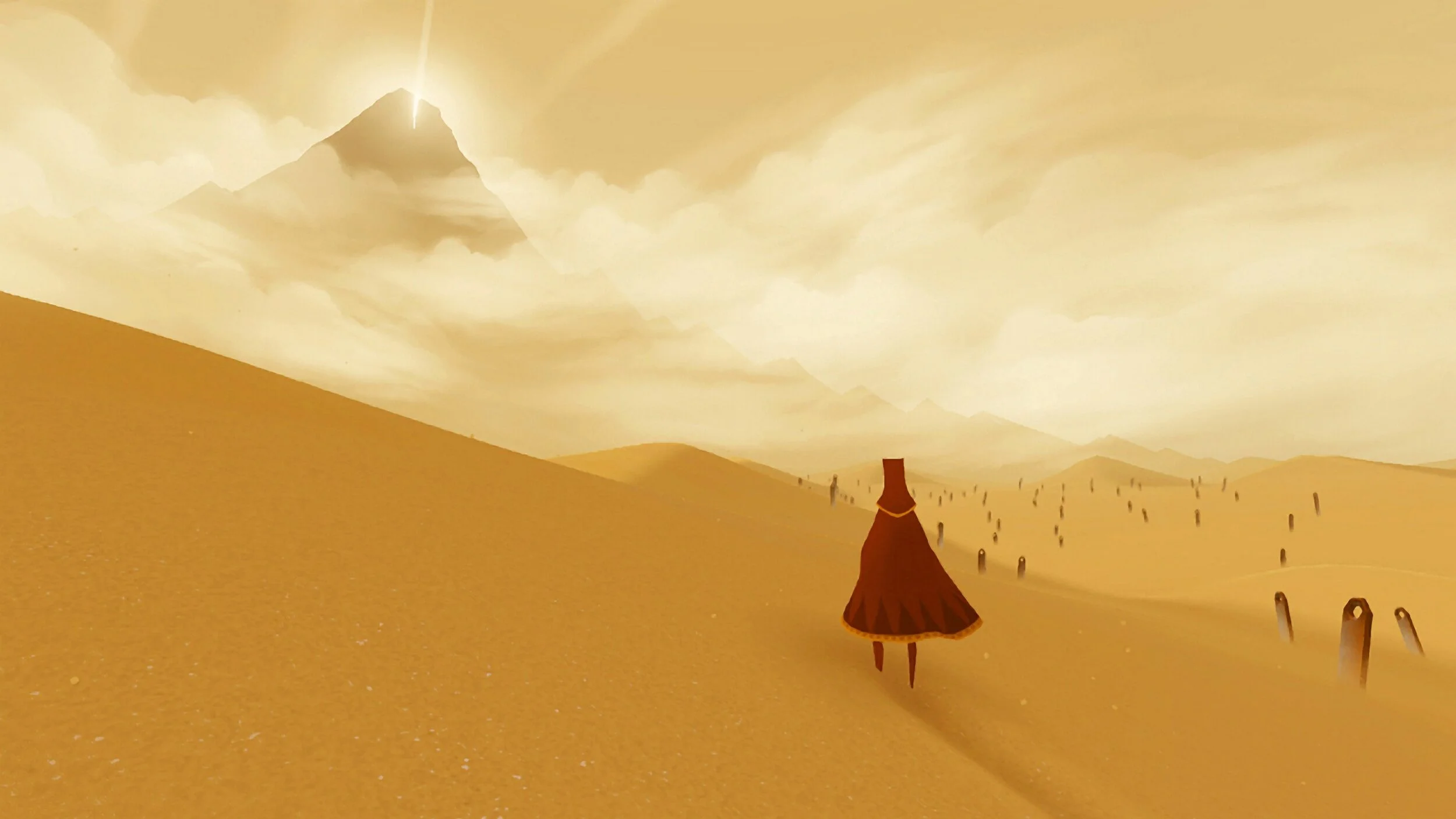

Physical memories

If there's one addiction that I seem to have no control over, and that's only getting worse with time, it's buying books. I love owning books. I love going to libraries and bookstores, and I love seeing our bookshelves at home fill up with new books to read.

For most of the posts I've written on this blog, I've been inspired by a book on our bookshelf. I pick up a book I read years ago, flip through the pages, and I'm immediately taken back to my experience reading it. I can vividly remember where I was and what stage of life I was in, especially for books that were transformative for me.

I think about this as we increasingly shift to digital tools, and I wonder what limitations we're placing on ourselves by moving away from paper. The vast majority of my documents and notes and to-do's live online, and there's no memory associated with them -- at least not the way there is with physical media. As someone who generally hates clutter, it would feel inefficient and wasteful for everything to live in print, so I don't think that's a viable solution. But it does make me consider what should live in the real world, and what is best online. Perhaps it's being intentional about which things would benefit from a deeper connection to them, and prioritizing their place in the physical world.

Deep work and success

There was recently a debate being had on Twitter about whether working long hours is a necessary component to having a great career. On one side, you had successful business owners arguing that their success would not be possible without working around the clock, and giving examples of well-known celebrities in the same boat. On the other side, you had successful business owners arguing that their success was possible because they took time to rest and work reasonable hours.

One of these successful business owners was Tobi Lutke, CEO of Shopify. His entire thread is worth reading, but this thought in particular caught my attention:

"For creative work, you can't cheat. My belief is that there are 5 creative hours in everyone's day. All I ask of people at Shopify is that 4 of those are channeled into the company."

There appears to be a lot of support for this idea. One popular source is the book "Deep Work" by Cal Newport. Newport proposes that focused work is the most important skill to develop, and says that we have a limit of about four hours of such work.

My own take on this is that there are many roads to a successful career, with different blends of creative and (for lack of a better term) "non-creative" work. While the amount of creative work per day may tap out at four hours, and lack of sleep affects further affects the quality of work, it's possible that success for some people was found by compensating for these concerns by putting time into areas that benefited from "non-creative" work. Success for others was found by leveraging their four hours a day of deep work into a valuable activity, and minimizing the remainder of the day spent on work.

Given these two scenarios, when looking for success, it's hard not to feel motivated to pursue the second example of those who most effectively leveraged their deep work. It likely requires significant work in understanding how to make your creative work valuable to others, but if the end result is a successful career and a well-balanced life, what more could you ask for?

H.A.L.T.

There is an acronym used by members of Alcoholics Anonymous called H.A.L.T. It stands for "Hungry, Angry, Lonely, Tired". The idea is that being in one of those four states makes you more likely to relapse on your commitment to sobriety. So, H.A.L.T. is a handy checklist of needs to address to reduce the likelihood of having an unwanted drink.

While HALT is a tool used by AA, it's a useful tool for working with any kind of addiction, especially and including addictive technology.

As consumers, we always have to be mindful when using addictive technology, but especially so when we are in HALT. While browsing social media can be a positive experience, it can also be a very negative one if you're feeling lonely. It's difficult as it is to prevent binge-watching a TV show, but mustering up the willpower to stop the next episode while you're tired is near-impossible.

And as designers, we have an equal responsibility to recognize when our users may be in one of these states, and be aware if our creations have the potential to generate an otherwise unwanted user behavior. If we can anticipate that a user may be in H.A.L.T. (based on factors such as time of day) what is our responsibility towards a user's time and attention? Being empathic and thoughtful in our work means supporting users at all times, especially when they are not completely at their best.

Keeping in touch

The best part of my job is the opportunity to work on meaningful projects with good people. And when we're not working, one of my favorite things is to have interesting conversations.

The reality of work, of course, is that people move on from their companies. The friends you work with for hours every day move on to new places, and the conversations change. And as much as we always promise to keep in touch, it doesn't usually happen. And if it does, the one part that's hard to replicate is those conversations -- the cumulative hours spent discussing ideas not directly related to work, but that make work (and life) that much more interesting.

That's where this blog comes in.

When I write, I imagine that I'm writing to any of my old friends that I don't see on a daily basis anymore. I imagine the types of conversations we might have had, and use that as a starting point for putting together something to say.

Of course, there are many more common (and less time-taking) ways to keep in touch than a blog. Social media has made it incredibly easy to quickly create and share bite-sized bits of content, which are more likely to be viewed by more people. But I think there is something unique about writing out ideas, both on the creating and the receiving ends.

In writing, I'm forced to distill my thoughts into something coherent enough to present in words. If it's not clear on the page, it's not clear in my head. This is likely a big reason why Amazon relies so heavily on one-page memos and written communication to drive their meeting, instead of presentations, and I think the results show in the company's success.

And, as a reader, I think reading blogs and writing in general gives me a different perspective than I'd otherwise attain. I get the sense that social media has made me know a lot less about a lot more people. If writing allows me to provide a deeper connection to even a few people, then I'm all for it.

Home work

When it comes to our projects at work, we tend to take them seriously. There are kickoff meetings, project plans, responsibilities, schedules, task lists, and a host of other activities to make sure we achieve the best result we can.

However, when it comes to our personal lives, things are a little more relaxed. We talk to our partners about projects only as they become necessary, we create resolutions that are quickly abandoned, and the most complicated planning tool we use is a wall calendar.

Many years ago I was fortunate to attend a training seminar by David Allen about his well-known time management book "Getting Things Done", and one of the things that stuck out to me was his suggestion to treat personal time as carefully as time at work. For example, he said that him and his wife have physical inboxes at home to communicate mundane information back and forth, such as bills and shopping lists, so that their limited time together in person can be spent on more interesting topics.

I've found success adapting this philosophy with my own partner at home. Like David Allen's inboxes, we use email and Slack for routine conversation so our time together in-person is more fun. We have meetings to talk about goals and projects, and do regular recaps to talk about how things are going and what could go better.

I think this approach will only continue to grow in popularity. A few years ago, I had the idea of creating a system to manage and keep in touch with personal contacts with the same guidance and regularity as salespeople keep in touch with their clients. Today, there are multiple apps that function as "personal CRMs". Basecamp is the best software for business teams to work together, and a few months ago they released their personal edition (for free! Go get it) for people to manage their households.

Ultimately, managing and giving personal lives with the same attention we give our work is a good thing. We've spent years making things easier, better, and more powerful in our work. Why not bring some of these great ideas home?

Design constraints, life constraints

As a parent of an almost-two year old, it feels like there's never enough time. There are only so many hours in the day, and finding time outside of work to exercise, prepare healthy meals, maintain a hobby, keep the house clean, stay on top of projects, and remain connected to others often seems impossible.

There are a number of tactics for dealing with the lack of time, such as asking for help, setting a schedule, and choosing to let certain things just drop. But there is also a strategy to deal with the overall problem, which is to use the same approach I use every day at work: to define this as a design problem. I have constraints (such as time, energy, and money) and goals (such as be healthy, provide for my family, and have fun), and the challenge is to achieve the desired goals while accommodating for the constraints.

What's encouraging is that a key theme in design is that constraints make the design better. When completing a design project at work, it can be frustrating to have limits such as time, the capabilities of the software we're using, or conflicting opinions within the team. But after working on enough projects, you begin to learn that all of these constraints make the work better, because a) you are forced to prioritize, which uncovers what you value, and b) thanks to time constraints, you are forced to actually deliver something.

I have a feeling this applies equally to parenting, and much else in life, and there appears to be some validation of this. In "The Obstacle is the Way", Ryan Holiday take us through a discussion of stoicism, and bolsters the idea that how we respond to obstacles (or constraints) is what defines us.

As a parent, this isn't much consolation in the moment while I'm sleep-deprived and there's a million things to get done. But remembering this mindset, especially since it is such a key component to what I do at work, gives me hope that it's possible to keep making things better, and deeply meaningful to keep trying to do so.

Typographic style in e-books

By all accounts, the Kindle should be the perfect device for me.

I love to read, but hate the clutter that physical books cause. I often read at night after my partner has gone to bed, but any book or table lamp keeps her awake (unlike a backlit Kindle). And thanks to Overdrive and my public library system, I can borrow thousands of digital books right from home.

But, after multiple attempts with multiple generations of Kindle, I still keep returning to physical books. Despite all of their shortcomings, I continue to borrow and buy physical books, and lug them around through hotels and airports.

It seems that I'm not alone. Physical books still vastly outsell e-books, and the majority of those buying physical books are actually younger readers.

The assumption is that people choose physical books because of beautiful cover design and photography, which is why fiction bestsellers tend to do better on electronic readers (like the Kindle) than highly visual material like cookbooks and children's stories. However, I think it may be more subtle than that.

One of the most influential books on design ever written is Robert Bringhurst's "The Elements of Typographic Style". It's well-regarded as the definitive book on how to arrange text on a page, and it goes into an amazing level of detail. There is a section on how the curvature of letters in a font reflects a period in time. There is a lengthy discussion on how to arrange paragraphs on a page, and how it corresponds to scales in music. There is even a review of the five (!) different types of dashes (-, –, —, ——, and ———) and when to use which one.

The point of all these details is that even for books without visuals, designers have a tremendous amount of decisions they can make when designing a book. When all of the decisions are made thoughtfully and carefully, the end result is a book in which the design fades away and your attention is completely on the content of whatever you're reading.

I think this is a tremendously difficult thing to achieve in Kindles or any e-readers. A Kindle takes a piece of text, and with very few options (font, spacing, margins, etc.) it presents the material. It must be an incredible challenge to take all of the thought of a well-designed physical book and translate that to a constrained e-book environment.

And I think that we pick up on that as readers, and find something slightly less pleasing about digital books. We talk about appreciable things like the smell of fresh ink and the feel of paper, but our brain picks up on all of the little design decisions like the curvature of the fonts and the length of the dashes, and subconsciously object if something doesn't feel quite right.

So it's a difficult challenge for e-readers, but also a worthwhile opportunity. While perhaps not all e-books can (and should) be designed with the care of their physical counterparts, there is an opportunity to do this for some of them, for those books that we would love to see come alive however we choose to read them. If this effort were put into place, I have a feeling we would notice.

Giving and growing

Perhaps it's because I'm Canadian, but for most of my career I've been given the advice to not be too helpful at work. Helping others is wonderful, the advice goes, but you have to look out for your own career first so that you're not taken advantage of.

So I was fascinated to discover Give and Take by Adam Grant. In this book, Grant investigates if it pays to be helpful. He begins by categorizing people as either a) "givers", people who primarily give more help to others than they expect in return, b) “takers”, who primarily look for benefit from others, and c) “matchers”, who try to keep in balance the help they give and receive.

What Grant found appears to validate the advice I’ve always been given: the least successful people in their careers tend to be the givers. They don't look out for themselves, and their own goals get sidetracked because all of their time is spent helping others. Takers and matchers, by contrast, tend to be more successful.

But, there's a twist. The most successful group of all is actually also the givers. Some givers actually tend to be the most successful of all — they are just the ones who are careful to avoid going out of their way for the takers.

This is tremendously inspiring. It tell us that we can be successful in service of others, with just a little bit of awareness towards who we're dealing with.

I'm curious to find people who've achieved great success in this way. I think one such person from my own field, design, may be Dann Petty. Dann is talented independent designer who keeps busy working with some big-name clients, but if you look at his Twitter profile it seems like he spends all of his time just helping other designers. He's constantly working to connect designers to his contacts with good job opportunities, he organizes events to connect disparate designers, and shares examples of good work and how to learn from it. Given the community he's built and success that he has had, I suspect he's figured out a way to have a great career by giving help and supporting others.